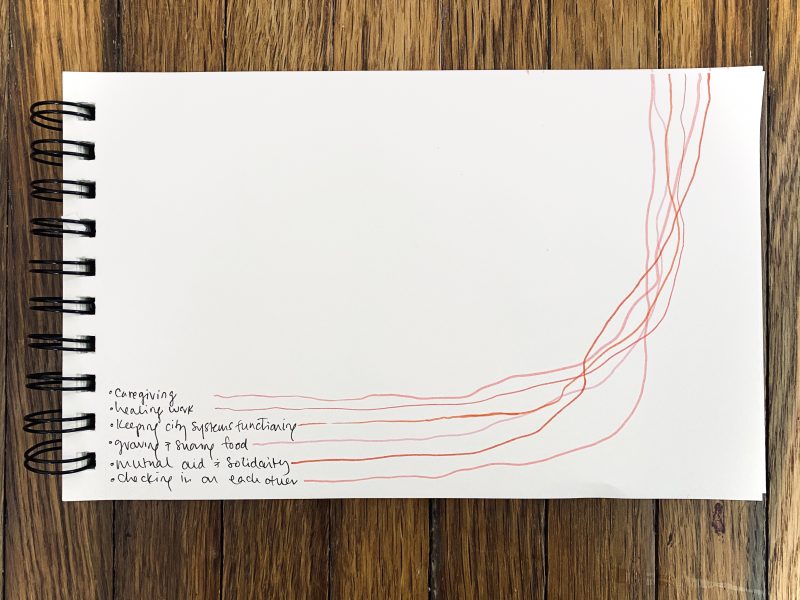

We ask you to join us in an exercise to reimagine our world from the stance of the future. How will the history of this present time be written? What world might emerge from this crisis? We are inviting public artists, writers, change-makers, and thought leaders to share their visions, which we will post to share with all.

8/13/20

I am asked to consider—what this place will be like in 2040?

By Sean Connaughty

“Water as pure and soft as the dews of heaven, gushing from hill and valley.”

Minnesota Pioneer, 1849

I am a person of mostly European descent. In 1962, my mother and father built a house in what is now the suburbs of Minneapolis. I grew up on a gravel road amidst prairie, forests, wetlands, and oak savannah. I watched and mourned as the land around us was sold. Surveyors staked out the land and the earthmovers arrived, leveling the land and building a city. I didn’t understand that I was part of the population explosion that began with westward expansion and Manifest Destiny. Painful as the loss was to me, I often wonder what it must feel like to be Dakota.

This is the sacred homeland and birthplace of Dakota peoples.

The ideology of Manifest Destiny resulted in the attempted erasure of Indigenous peoples and cultures and an incalculable human and ecological toll. Late in understanding, I just realized that mainstream culture continues to follow this doctrine even today, not only in terms of continued social injustices. The ecological toll of this doctrine also continues, with urban development expanding outward in growing concentric rings, consuming the land that is now our suburbs, exurbs, and beyond. Every day more land is consumed. The wetlands, forests, and prairies along with their wildlife inhabitants, are absorbed in the ever-growing thirst for more space, more resources, and more consumption. We remain convinced that is our right to do so. It was inevitable that the result of this would be the imbalance we now face.

We are now called to restore balance. I’ve been imagining ways to do this in my own local community, as have others. To restore some of what we have lost. I started thinking about this a while ago as I’ve been doing my work at Lake Hiawatha. It’s a small lake in my South Minneapolis neighborhood. It is a site of great biodiversity yet suffers from excessive anthropogenic impacts. (Link to Stewardship Report)

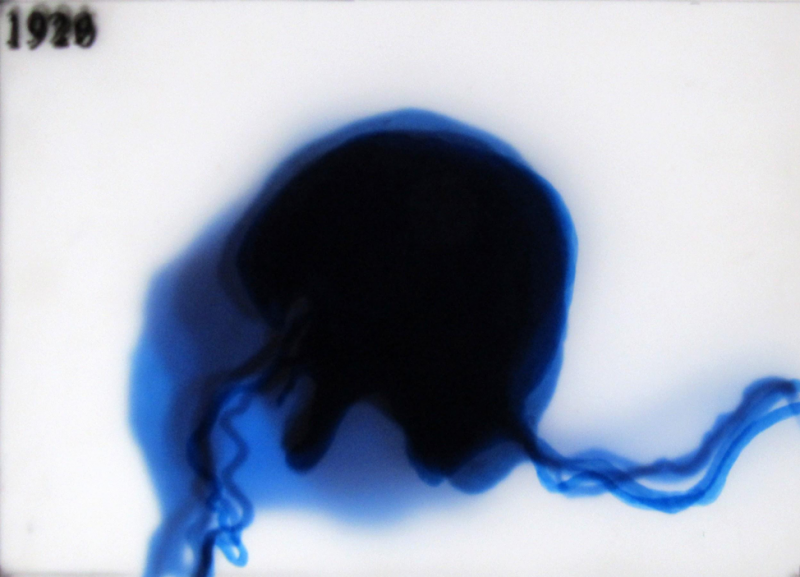

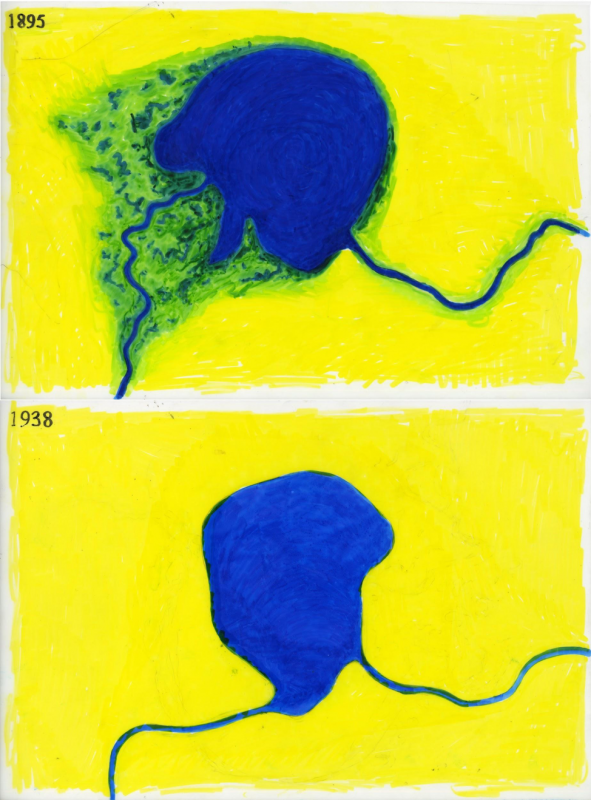

In 1929, what was once called Rice Lake was transformed into an entirely anthropogenic space through a massive engineering effort that removed all traces of habitat and wetlands from the Lake. It was renamed Lake Hiawatha.

Over the 90 years since that transformation, ecological forces have recovered a portion of the space. This is the area that my work is currently focused on with the potential of expanding its reach through the forthcoming reconfiguration. Because the Earth is resilient, she has rebuilt some of what she needs—a new delta wetland habitat formed where Minnehaha Creek meets Lake Hiawatha. I have recorded 90 species of animals (and counting) that have returned to live in this little area that was formed over the last 90 years since the change (link inaturalist). After we removed more than 7,000 lbs of plastic and Styrofoam trash from the Lake (link trash survey), I was given permission to work with the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board on restoring the Lake Hiawatha Delta Habitat through management and native plantings. I’ve also been working with Friends of Lake Hiawatha and Healing Place Collaborative (HPC), who have recommended plants to restore to this area. HPC also partnered with me on my recent exhibition Lake Hiawatha – Anthropocenic Midden Survey – Final Report (link to Exhibition Summary) and other public programs about Lake Hiawatha to hold conversations about the history, present, and future of Lake Hiawatha from a Dakota perspective. An exhibition at White Page Gallery in November 2019 also included activities with Healing Place Collaborative, artist Graci Horne, Ironwood Foraging, and Waterbar.

SOLUTIONS

- No Net Loss – Habitat Policy

What if we change our view to regard each ecosystem as sacrosanct and work to generate new ecosystems by utilizing public and private spaces to develop contiguous habitat throughout the city? We could re-wild or naturalize spaces that are underutilized or abandoned. A policy could be put into place that stops the consumption of remaining habitat. Incentives could be offered for the development of new habitats. Key zones would initially attract more attention because of their proximity to major existing habitat zones and water bodies. We could create land bridges across freeways and highways to connect fragmented habitat spaces. Residential and business lawn spaces and urban agricultural spaces could become habitat.

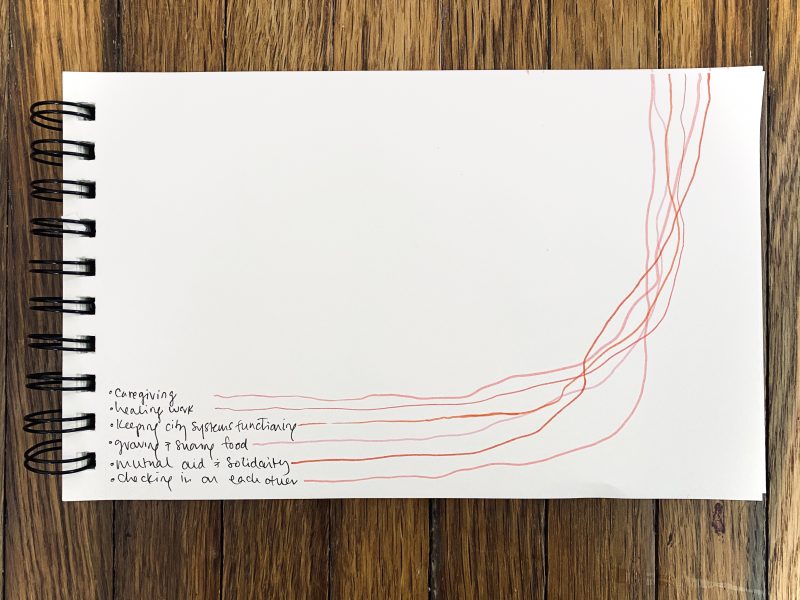

- WPA Minneapolis and St Paul 2.0

On the national level, we see leaders proposing the Green New Deal. We also know change at the national level will take some time. Locally, what if we created a work program in our cities to address local problems and opportunities now? People need work, and there is much work to be done. We can begin this work ourselves. Maybe the Parks, Watershed Districts, City, County and possibly the State, can collaborate to commission a jobs program to do the work that needs to be done (in no particular order):

Reconnecting fragmented ecologies

Stormwater treatment

Repairing infrastructure

Naturalizing and re-wilding public and private spaces

Wetland development

Community gardening

Cleaning trash and plastic debris from bodies of water and streets.

Repairing businesses and properties damaged during the recent uprising about George Floyd’s murder

Local food production and distribution

Creating homes for the homeless

Conflict resolution and de-escalation—and more.

We can finally put to rest the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and establish a safe and just community that is self-sufficient and lives in a reciprocal relationship with the Earth.

BIO

Sean Connaughty’s socially engaged art projects address anthropogenic impacts on global ecology and humanity’s place within that system. By working with communities and agencies governing our public spaces and infrastructures, he uses public art as a catalyst for mitigating damaging behaviors. Recently, Connaughty received a 2017 Forecast Public Art development grant for his Lake Hiawatha Visioning Project, a 2018 McKnight Fellowship, and in 2016 had a solo exhibition at the Weisman Art Museum featuring his collaborative project Anthropocenic Midden Survey—Mississippi River. A graduate of both Minneapolis College of Art and Design and the Savannah College of Art and Design, Connaughty is a lecturer in the Department of Art at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities.

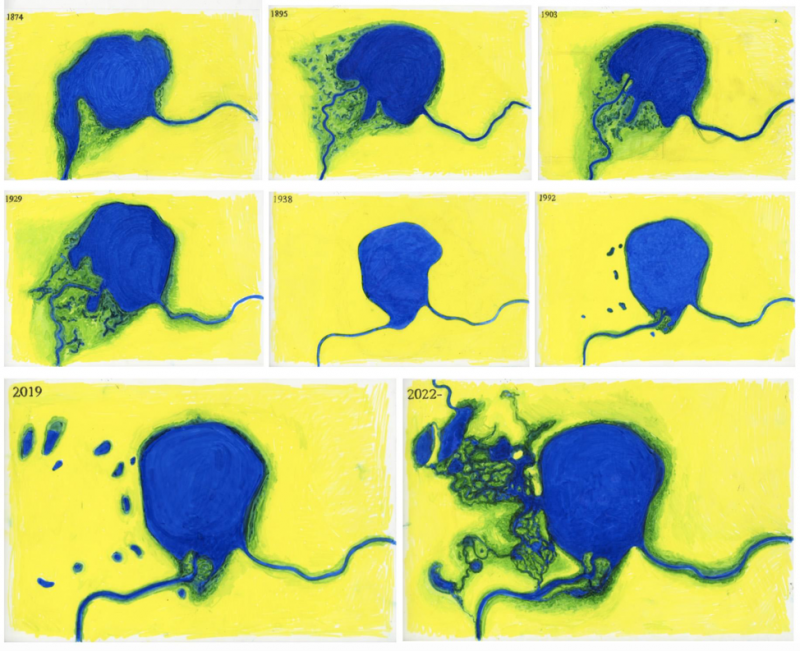

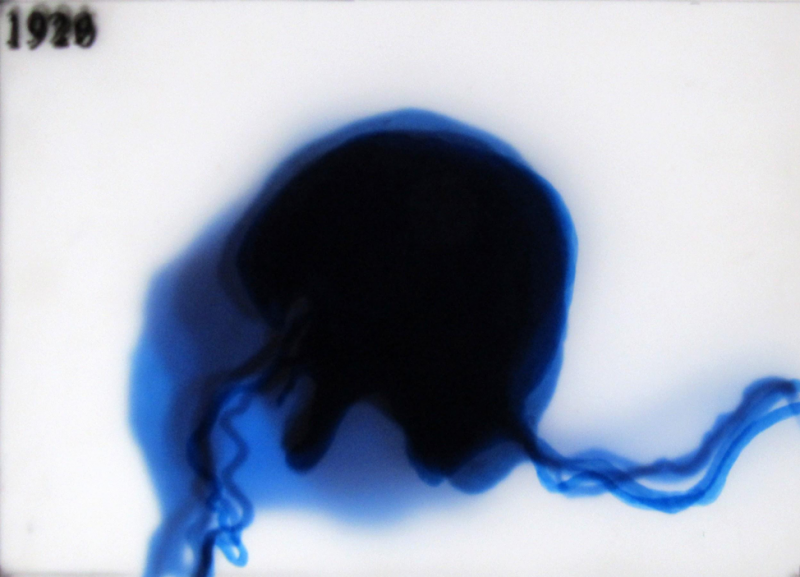

“Rice Lake/Lake Hiawatha Watermap 1856-2019” Sean Connaughty 2019 ink on mylar – backlit. 9×12” ea.

This series of ink drawings on frosted mylar originate from studies of historic maps of Minneapolis and show the adaptability of Rice lake/Lake Hiawatha prior to the dredging and filling of wetlands in 1929.

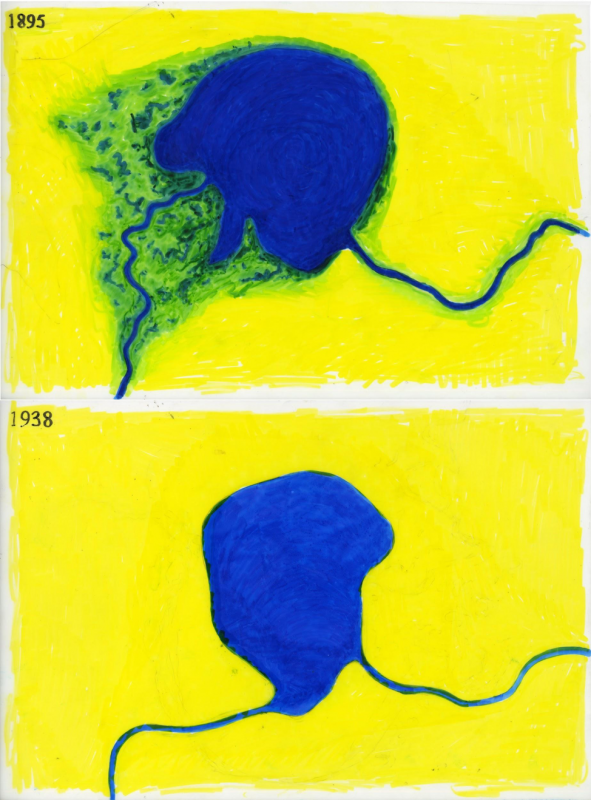

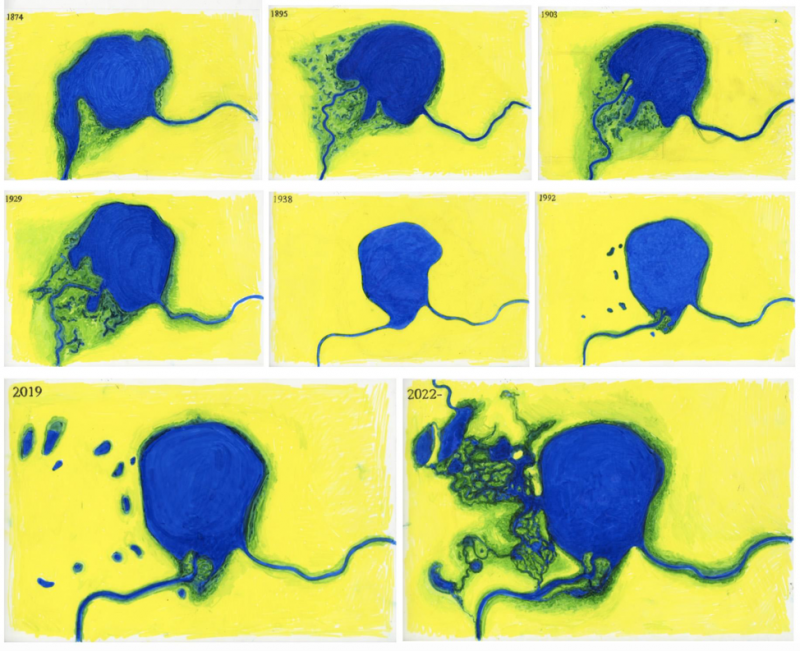

Above: “1874-2022 Rice Lake/Lake Hiawatha Wetland watermaps” ink on frosted mylar 11×17” ea. Sean Connaughty 2019

Based on study of multiple historic terrain maps/drawings from 1874-2019 the 2022 is a projection based on current MPRB (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board planning. The drawing shows the adaptive transformation and variation of Rice Lake prior to the massive engineering of 1929, when all wetlands were removed from the area.

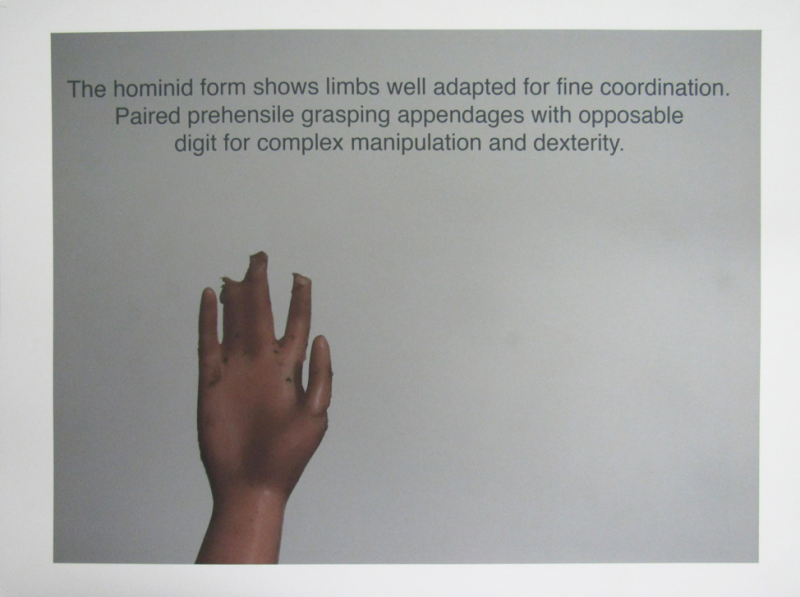

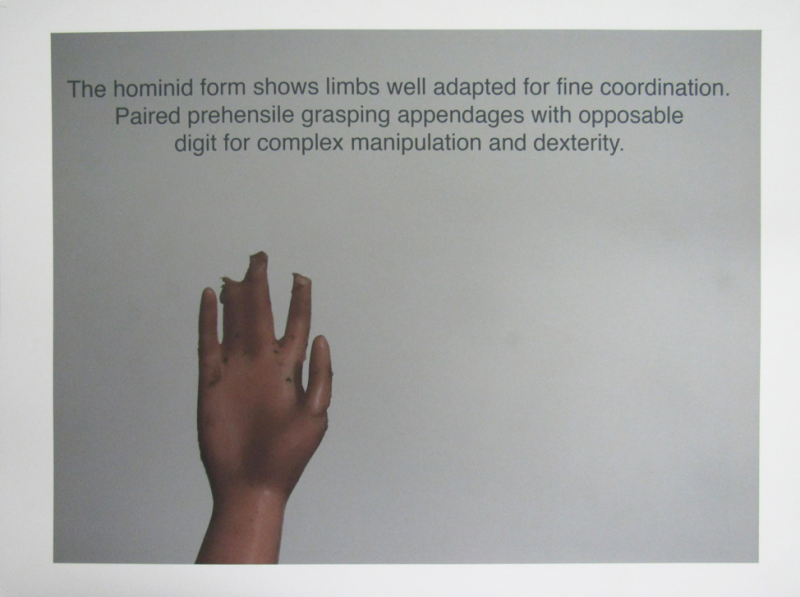

Above: “Anthropocenic Midden Survey – preliminary report -panel 2” (multimedia presentation excerpt) digital print on rives BFK paper. 22×30”ea. Sean Connaughty 2016.

An archaeological report is made from the vantage of the distant future where the waste legacy of humankind is studied by another culture. The report attempts to glean an understanding of our culture, while lacking the Earth based context we take for granted the future archaeologists learn that our culture was at a tipping point of climatic and ecological disaster. www.vortexnavigationcompany.com

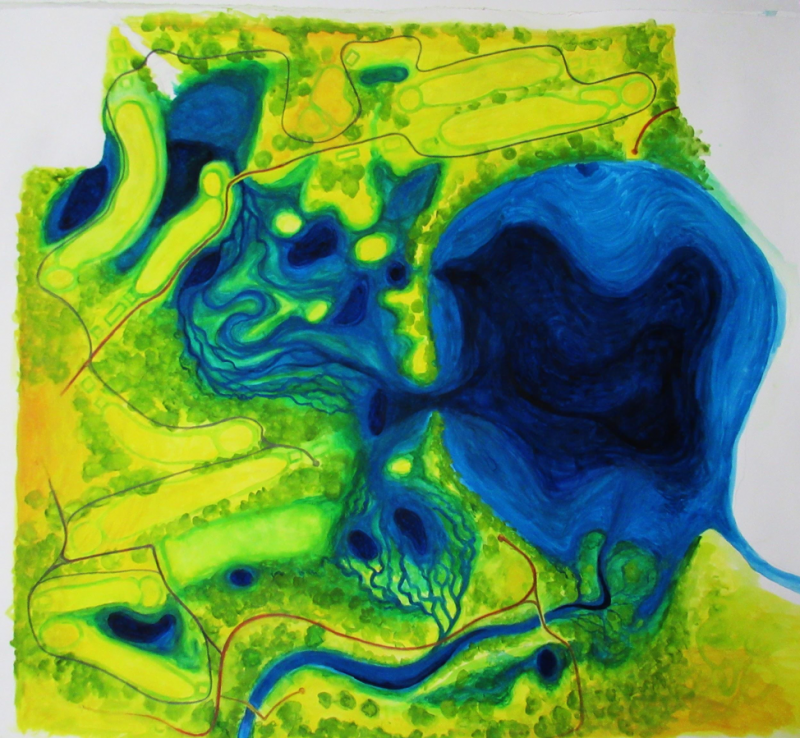

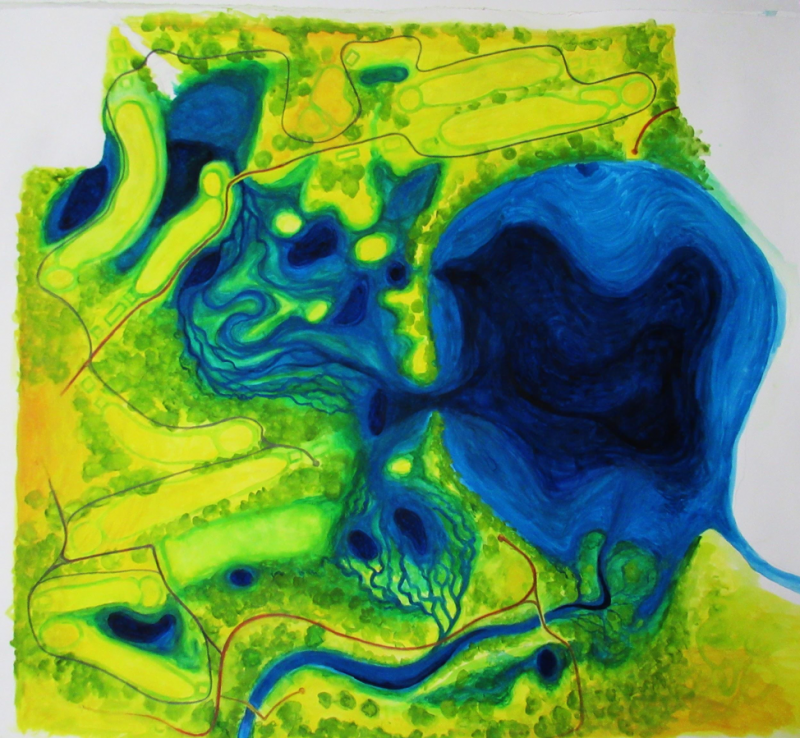

“Lake Hiawatha Watermap -Response to MPRB Concept 2” gouache on paper 60×60” 2019

This drawing is the result of years of study of Lake Hiawatha. It is a visual statement or recommendation to the MPRB (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board). Drawings were submitted digitally and in person on multiple occasions both at community meetings and in discussions with MCWD, (Minnehaha Creek Watershed District) City of Minneapolis, Public Works and Mayor Jacob Frey. The drawings are responses to proposed plans put forth by the MPRB. Consulting with members of Friends of Lake Hiawatha, we made adjustments to the MPRB Concept plans through this visual comment.

6/17/20

Park Bench

By Boonmee Yang

“I don’t care if you go out without a jacket and hat but bring your face mask!” yells my uncle. I hear him turn on the blender to make our pepper sauce. “Thirty minutes—max. If you’re not back by then, I start dinner.” Anyone eavesdropping might think he means it, but he always waits.

Siabzoo’s already at the park when I arrive. He gets up, and we air hug from six feet apart. I sit on the bench across from his, the unshoveled sidewalk our familiar divide. “Miss you” is written in the snow beside him.

“Can’t wait for spring. I hate quarantining every winter,” he says. I scout the area as he takes off his face mask, kissing the front of it before throwing it to me. I do the same. The thrill of getting caught exchanging our cloth masks is why I never need a jacket. It’s one way we stay intimate, no one suspecting the same colors.

“My uncle says winters were different 20 years ago,” I say. “People could still go out and do things. Imagine that.”

“My mom says no one saw it coming when the virus mutated with the flu.”

“Yep,” I say.

“Same time tomorrow?” He gets up and moves towards me, raising my heartbeat. I shake my head. “We should really move to a warmer state when we’re older. They don’t have this problem.” He blows me a kiss.

“Bye, Lue.”

“Yours until,” I say.

“Until forever.”

Boonmee Yang is a full-time English Language teacher who loves seeing his students see themselves in the text they read. For that reason, he values reading and writing texts reflective of his students’ home experiences, including names that are familiar to them and truths they’ve always known: that they are worth centering stories around. What drew him to “Future Past” was the opportunity to write and continue normalizing these characters and stories, by setting them in a future where their names and relationships are just as commonplace as the new norms of societal practice. He lives in St. Paul.

In consideration from my next future: What Gwendolyn Brooks taught me about tomorrow’s geography

POSTED 6/4/20

I wrote this letter two months ago by invitation as a part of a series of writing that was coming out of North News in reflection and response to the Coronavirus pandemic, a virus which infects the respiratory tract. I wrote it in consideration of reckoning with and looking beyond a world in which black breathing is an impossibility, an impossibility through which whiteness, which is to say the categorical distinction of the human, coheres itself. This was before (if you believe in such orderings of time) George Floyd had the life choked out of him by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin in broad daylight, in front of witnesses. It was not an anomaly. There are no bad apples here, it is a rotten tree. This letter, written affectionately for those impossibly breathing, is being republished, as a part of Public Art Saint Paul’s Future Past series.

Warmly cw.

Future Reader,

I am writing this from my kitchen table, the chatter of three of my and my partner’s four children in the background. One of them is building a lego-house, their architectural design a thousand miles from functional, but so full of imagination and their unique creative touch. I am writing this from my kitchen table, watching my child and wanting to feel as free to be a thousand miles from functional. As I watch them I feel the constraint of time, I sense my own practiced subscription to its ubiquity, its bordering logic. This so-called progressive phenomena giving rise to a compression felt in my body—sometimes as a shortness of breath, other times the cold sweat amassed from the fear of all I haven’t done.

Time is my full inbox, the meals yet prepared, the proposals unwritten, it is the swelling in my throat at the magic I must perform each month with thin money and thick bills. “Crisis” heightens this. When is other than crisis? Other than austerity?

I am writing this from my kitchen table returning to one of my holy texts by Gwendolyn Brooks, her autobiographical, Report From Part One. I am thinking of how Brooks, the Pulitzer prize winning poet, had her lights cut out when she found out about the award and wondering if she too felt the cold sweat of time? In the appendix of Report From Part One, its additional matter, Brooks writes:

My aim in my next future, is to write poems that will somehow successfull “call”… all black people.[i]

So succinct as to almost be hidden, Brooks tells us she is writing from one of her many futures. That in her next future she’s got plans for the poems she intends to write. Here I read Brooks’ embrace of the plural, the multiple, with regard to time, which is to say a refusal of history as chronology, as universal.[ii] With this reading there are many Gwendolyns, and many futures, other possible worlds in which they might live and write and are perhaps even living and writing.

I am writing this from my kitchen table considering what future this might be from, how the consideration of this being written from one of my futures disturbs times supposed linearity. I am writing this wondering if in my next future, which, from one interpretation of Brooks, could have preceded this one, I will have more clarity about my own survival, about the conditions of that survival in a world predicating its impossibility. Here I think of our Lorde, her articulation of how “we were never meant to survive”,[iii] that modernity itself kicks off with black disposability as a principal technology. The question is, how to go about living in a world founded on your dispossession? To do so is its own kind of anarchy, black living, a queer and radical thing[iv].

Brooks was writing Report From Part One from a future[v], and that, not as some far off landscape. Those futures seemed to run through her as a part of her cellular makeup. What might it mean to be from the future? Who will I “call” which is to say with whom will I be in conversation, in mutual aid? What worlds make such sociality possible? I am writing this from my kitchen table, from one future, not in response to a virus, I am writing this in consideration of what it means to be human if we should have any investment in that categorical distinction at all. I am writing this wondering if one future might spill into another into another. How in moments when it seems like the world may be ending that we might do well to remember a future when it ended before. That Aimé Césaire would suggest that that “end”, “of the world no less” is the only proper place to begin[vi]. And this is not to propose doom, this is to suggest that doom is where we are, it is to propose that this current world and its logics have brought disaster and that that world cannot continue, it is a stubborn belief that other worlds are not just possible, they are here.

I am writing this from my kitchen table and considering that this is a report also, from what part I am not sure, but somewhere in the additional matter of this future there may be instruction around the kind of being that we would consent to. I am writing this not to convince you, reader, from whatever future this finds you in. I am writing this as signal, as call from in and beyond the crisis. Because in my next future, I desire a future past where I intend(ed), however impossibly, to survive.

This piece by Chaun Webster was originally published in North New (Minneapolis) on April 15, 2020. Reprinted as part of Future Past with permission from the publisher and author. Public Art Saint Paul thanks North News for sharing this piece with us.

https://mynorthnews.org/new-blog/chaun-webster

[i] See Report From Part One (183).

[ii] See Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research And Indigenous Peoples (31)

[iii] See Audre Lorde’s, The Black Unicorn (32).

[iv] See Alexis Pauline Gumbs introduction to Revolutionary Mothering: Love On The Frontlines where the speak to Black women’s use of literary production between 1970 and 1990 as a way to “answer death with utopian futurity” and that to do so was “an outlawed practice, a queer thing.” (21)

[v] For more on the use of future(s) and queer temporalities see Kara Keeling’s Queer Times Black Futures.

[vi] See Aimé Césaire’s Return to My Native Land (39).

POSTED 5/18/20

The Time of the Beads

by Andrea Carlson

Beaded moccasin trim made by Marisa Carr (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe) during the 2020 shelter-in-place order in Chicago. Photo: Marisa Carr

Beaded moccasin trim made by Marisa Carr (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe) during the 2020 shelter-in-place order in Chicago. Photo: Marisa Carr

When the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe was devastated by the Spanish Flu in 1919, an Ojibwe father had a dream of the first Jingle Dress that became medicine, used to heal his daughter. In 2020, one-hundred years after the inception of the Jingle Dress, another pandemic swept through Ojibwe Country. While dance had been our medicine before, slowing the spread of COVID-19 required that the Original People suspend all social dances. So we went indoors and beaded.

We beaded and posted our creations on social media. We applauded each other’s work and created desire for ourselves by ourselves. We video-conferenced with each other and used this media to teach new beaders how to bead, and new dancers how to dance, and new language speakers how to speak Ojibwemowin.

The beadwork made during 2020’s shelter-in-place order resulted in a boom of dance regalia. The excess of moccasins, earrings, hair ties, yokes, and leggings were gifted to family members who could not afford them before. When the pandemic subsided, new dancers emerged all over Ojibwe Country wearing new floral beadwork in stunning colors. This special time in our history is now remembered as Manidoominensag Ningoding (The Time of the Beads).

It is hard to imagine now in 2040, but there was a time when most non-Ojibwe people didn’t know what Ojibwe floral beadwork looked like. Now non-Ojibwe people can respectfully identify Ojibwe things without appropriating them.

Our survival was so robust that we had the power to insist that our practices not be co-opted by those who have long displaced us. The space that we have reserved for ourselves is a continual healing place.

About Andrea Carlson

Andrea Carlson (b. 1979) is a visual artist currently living in Chicago, Illinois. She maintains a studio in St. Paul and is represented by the Bockley Gallery in Minneapolis. Through painting and drawing, Carlson cites entangled cultural narratives and institutional authority relating to objects based on the merit of possession and display. Current research activities include Indigenous Futurism and assimilation metaphors in film. Her work has been acquired by institutions such as the British Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the National Gallery of Canada. Carlson was a 2008 McKnight Fellow and a 2017 Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors grant recipient. For further inquiry, see artist’s website at https://www.mikinaak.com/about

POSTED 4/30/20

Reflection—2040

By Shanai Matteson

A couple of weeks ago, during a public artist talk that had been moved online because of Coronavirus closures, I was asked a question about hope.

Where do I find hope in these turbulent and grief-stricken times? What keeps me working toward futures I can only imagine?

I had to think about this question, and if I was ready to answer it unequivocally.

I’m still not sure.

When Public Art Saint Paul asked me to write a reflection on the future—to imagine the sorts of evolutions in our culture and society that might emerge from our current crisis and response—I was similarly conflicted.

That’s because each day, I experience wild swings between hope and despair.

For every hopeful future, I can begin to imagine, there’s an equally despairing one, including a future where we go back to “normal” as quickly as possible, and nothing substantially changes.

Sometimes, I think we rush too quickly to focus on our hopes and the futures we can imagine, searching for the “good” amid the “bad”—or an inspired vision.

When we do, we risk carrying with us our assumptions that hope is like a silver lining—something positive we glean from the edge of heartbreak and hardship.

Despair, on the other hand, is overwhelming and heavy—a feeling many of us try to move through as quickly as possible.

This crisis is transformative for me, because this experience of hope and despair—which I’ve been having for a while in response to the reality of climate change—is widespread and collective.

It’s happening all across the country and globe, and it seems to be catching many by surprise—like a curtain pulled back, revealing what we try to keep buried beneath our busy lives:

Our fears of not-enough. Our fears of death and loss. The feelings of emptiness and anxiety that creep in when old certainties become uncertain and the future seems even more impossible to predict than it was before.

One thing I’ve noticed in my conversations with others over the past weeks is that this collective experience is triggering individual memories—times we’ve experienced scarcity, unplanned isolation, sickness, the death of loved ones, other heartbreaks and uncertainties.

We do need hope, because hope can motivate us to keep working toward a goal—but lately, I’m more interested in how we honor the wild lessons that come when we give ourselves time and space to grieve.

It seems wrong, at this moment, for me to write about the potential positives that could stem from a pandemic which is disproportionately harming those who already suffer from structural racism, economic violence, environmental injustice . . . to write about my hopes, while I’m able to shelter safely at home.

We’re witnessing the breakdown and failure of the social, political, and economic systems that have governed our lives. We’re seeing how these systems are shaped by a culture of death, and we are witnessing death—of human beings—and of old stories.

At the same time, we’re also witnessing the persistence of life and care. This is evident in the caring relationships between people and within the natural world. People are finding all kinds of ways to care for each other, and other-than-human life is also responding to our slower pace and shuttered economy.

At this critical point—which some have called a portal—the interconnections between how we live and what lives are more apparent. There is certainly hope here.

But the possibility is also heightened for increased harm in the near-term, as those in positions of power try to take control of the situation.

Our hope can’t just be a shortcut through the muck, it has to motivate us to muck in further.

For me, hope and despair are part of the same process: A reckoning with the nature of life and death, with the fact that much of it is really outside of my control, and with my own ability to have an impact anyway, no matter how small or intimate.

Hope is a feeling I get when I choose to be a witness to these realities and to give or receive life-sustaining care as I am able.

When I consider what this moment can mean for our future in 10 or 20 or 50 years, I think we will probably continue to oscillate between these visions.

At the same time, I believe that the number of us who reject a culture of domination and death and choose reciprocity and care can grow as exponentially as the graph we see tracking a virus.

As artists and creators, what would happen if we turned more of our energy and vision to finding ways to help ourselves and others grieve the death of old (broken, unjust) stories and systems, while imagining futures where the value of sustaining life and caring for others (including other-than-human beings) is central to our work?

I don’t have a sweeping vision of what that would look like, but the possibility compels me to move more slowly, to pay closer attention to the feelings that arrive, and to be tender and intimate with others.

This is where I choose to start each day, and what I will keep coming back to as time goes on.

Shanai Matteson

Shanai Matteson is an artist, writer, activist, and community organizer working in the Twin Cities and in northern Minnesota, where she grew up, and at the national level. With a diverse practice that includes environmental art around water and extraction industries, community care and repair, and social engagement, Shanai created “Water Bar and Public Studio” (with partner Colin Kloecker), a participatory space where people sample flights of water from different sources like fine wine, and engage in discussions about water and how we care for it. Water Bar has been presented at art museums, such as Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Bentonville, AR; at art festivals such as Northern Spark; at the EcoExperience Building at the Minnesota State Fair, and at numerous other events. Water Bar also functioned as a storefront space on Central Avenue in NE Minneapolis for several years. Shanai has recently launched “Raft” as both an in-person and online gathering space for people interested in working with others to learn about water and climate. Shanai was Co-Director of Public Art Saint Paul’s City Art Collaboratory and editor of an anthology of essays, Meandering Methodologies, Deviant Disciplines: Four Years of the City Art Collaboratory (Public Art Saint Paul, 2016).

POSTED 4/16/20

FUTURE PAST PRESENTS

WING YOUNG HUIE

FUTURE PAST presents Kid’s Cook Program, Loring Elementary, North Minneapolis by Wing Young Huie. He writes “This photograph is one of the most joyous I’ve ever taken in my 40-year career. We live in a polarized time. Hopefully, society will someday evolve to the level of these 2nd graders.”

Wing Young Huie has forged a distinctive photography career over more than 40 years. Wing has captured the complex cultural realities of American society. His practice encompasses public art projects that span miles, such as The University Avenue Project created with Public Art Saint Paul along 6 miles of this major street in 2010, and Lake Street USA in Minneapolis. His work has been shown in international museums -over half a million people have viewed his traveling exhibition in China- and in Minnesota storefront windows. His projects explore a myriad of social issues, including immigration, race, adoption, urban and rural life, dementia, faith, Lutheranism, gender, homelessness, and youth culture. Though much of his work centers on his homeland of Minnesota, his recent series “Chinese-ness” explores experiences of identity in the United States and the Motherland of China, employing documentary and conceptual conceits, and occasionally a chalkboard.

Wing uses photography as a societal mirror and window, seeking to reveal not only what is hidden but also what is plainly visible and seldom noticed, providing a collective portrait of the them who are really us. As an extension of his public art installations that create informal communal spaces, in spring 2011 Wing opened The Third Place Gallery on Chicago Avenue in South Minneapolis. Housed in a building that previously sat empty for 47 years, Wing has turned the space into an urban living room for guest artists, social conversation, karaoke, and ping pong. In 2018, Wing was named the McKnight Foundation’s Distinguished Artist, one of the highest honors for a Minnesota artist.

Beaded moccasin trim made by Marisa Carr (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe) during the 2020 shelter-in-place order in Chicago. Photo: Marisa Carr

Beaded moccasin trim made by Marisa Carr (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe) during the 2020 shelter-in-place order in Chicago. Photo: Marisa Carr